Catalog published on the occasion of the solo-exhibition of Johan Creten's "I Peccati" at Villa Medici in Rome, in collaboration with the Académie de France in Rome - Villa Médicis, Almine Rech, and Perrotin Galleries.

“I PECCATI”

Académie de France in Rome - Villa Medici

Rome

Italy

2020

With “I PECCATI”, the eponymous catalog of the exhibition presented at the Académie de France in Rome - Villa Medici, Johan Creten orchestrates a collection of iconic works from his career.

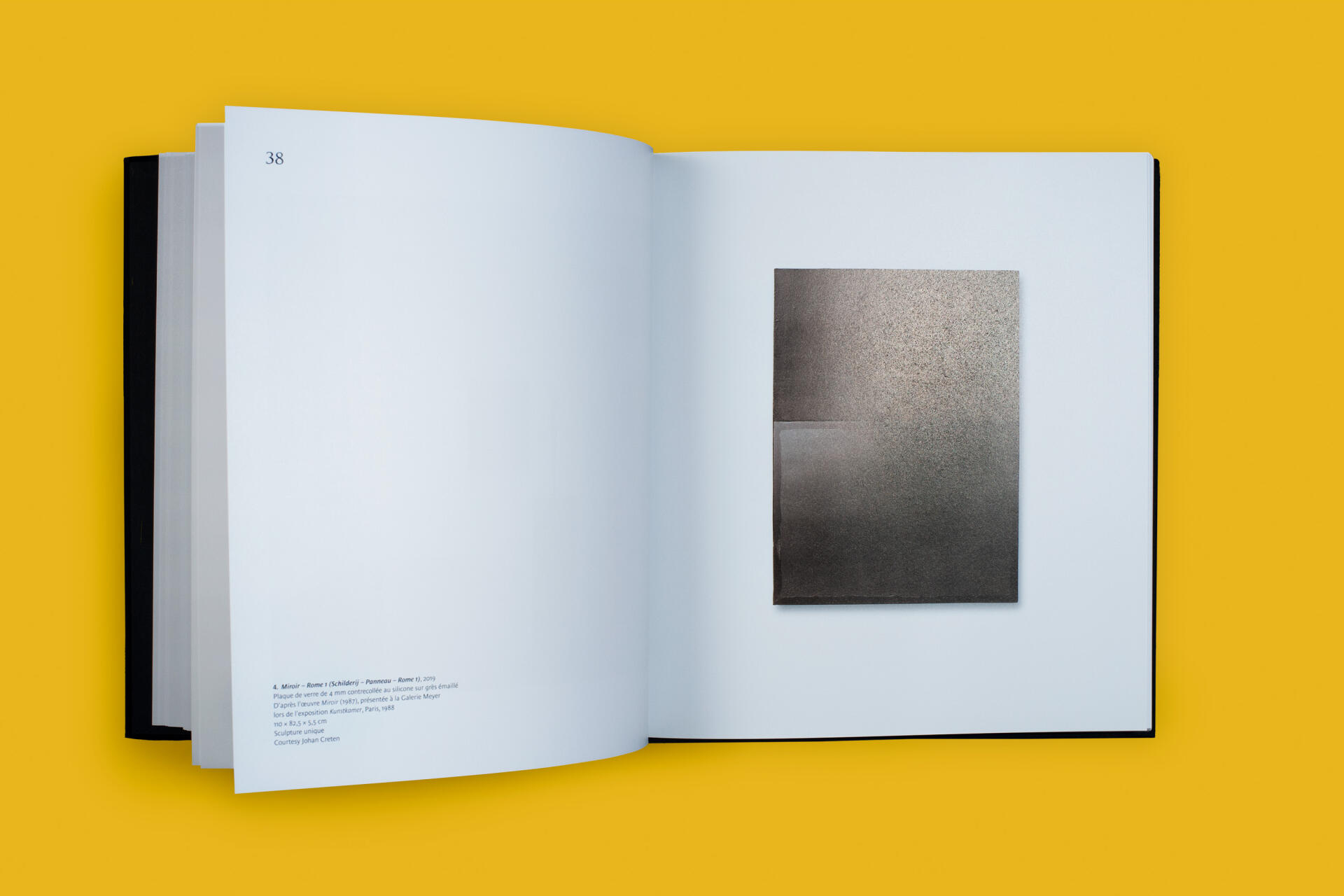

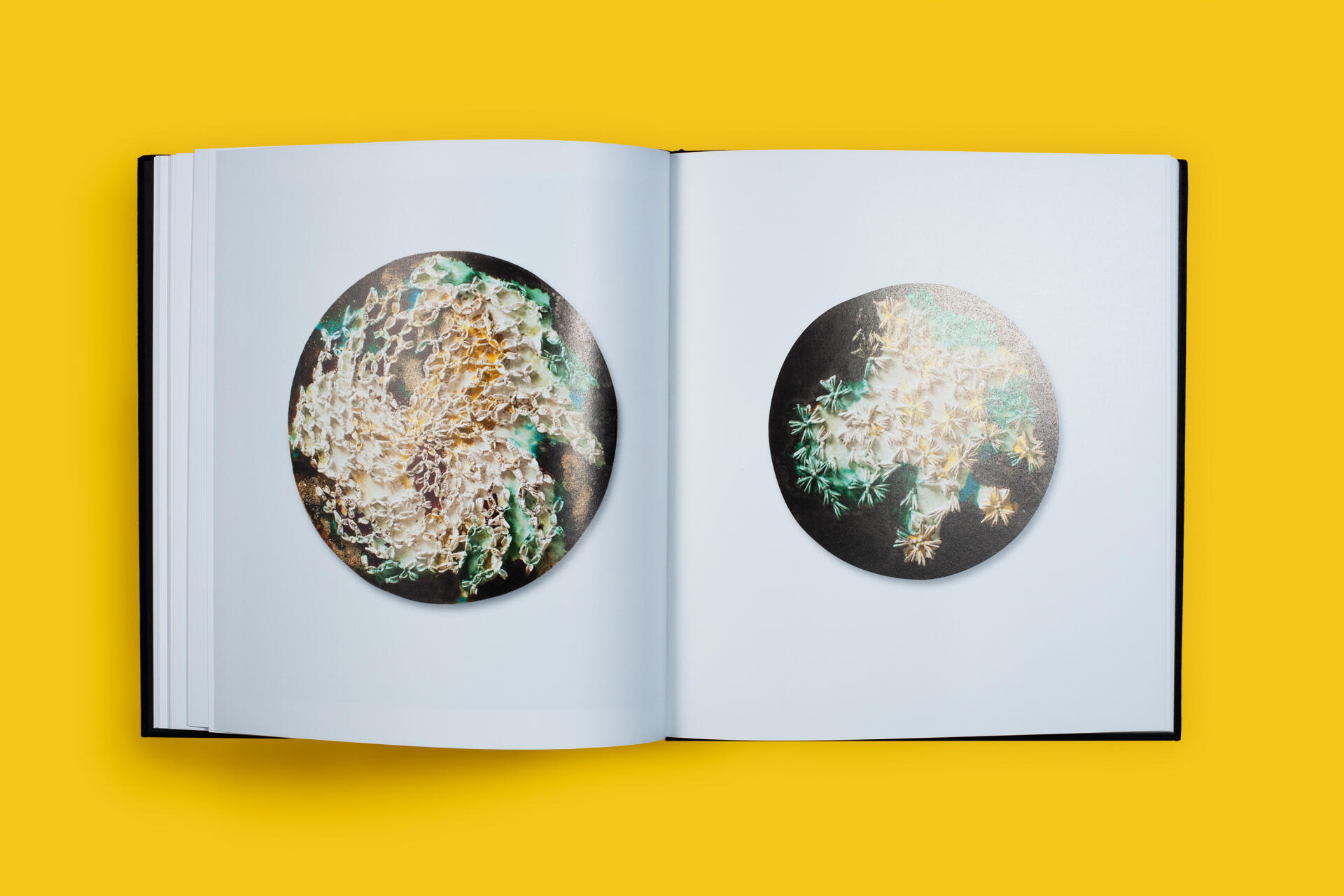

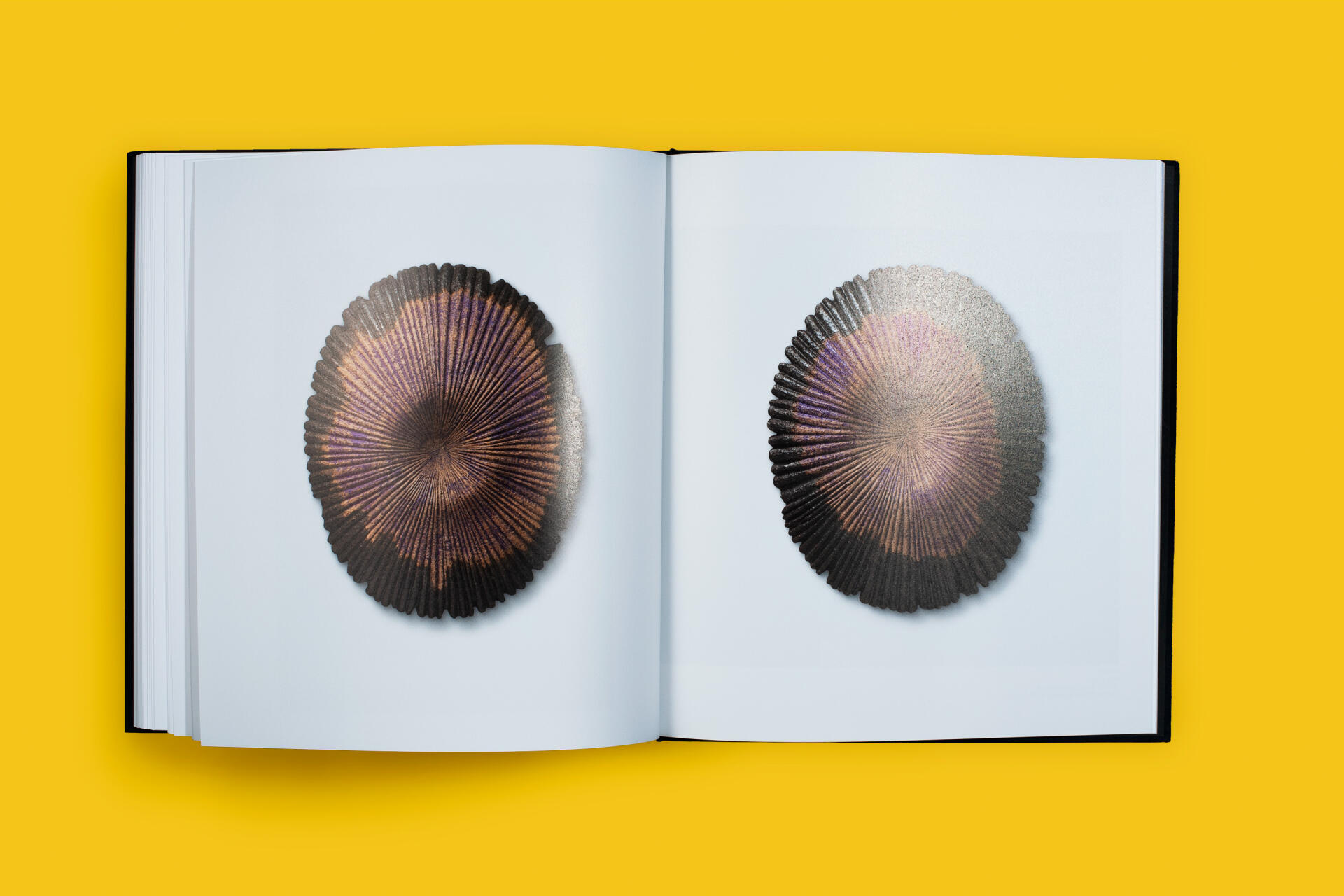

Conceived in collaboration with Noëlle Tissier, curator of the exhibition, “I PECCATI” brings together, for the first time and on such a large scale in Italy, a group of fifty-five works testifying to the artist's sensitivity in the face of the profound changes in society and a moral conscience that is more than ever shaken. Alongside his works in bronze, ceramic and resin, the artist presents a selection of historical works from the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, from his personal collection.

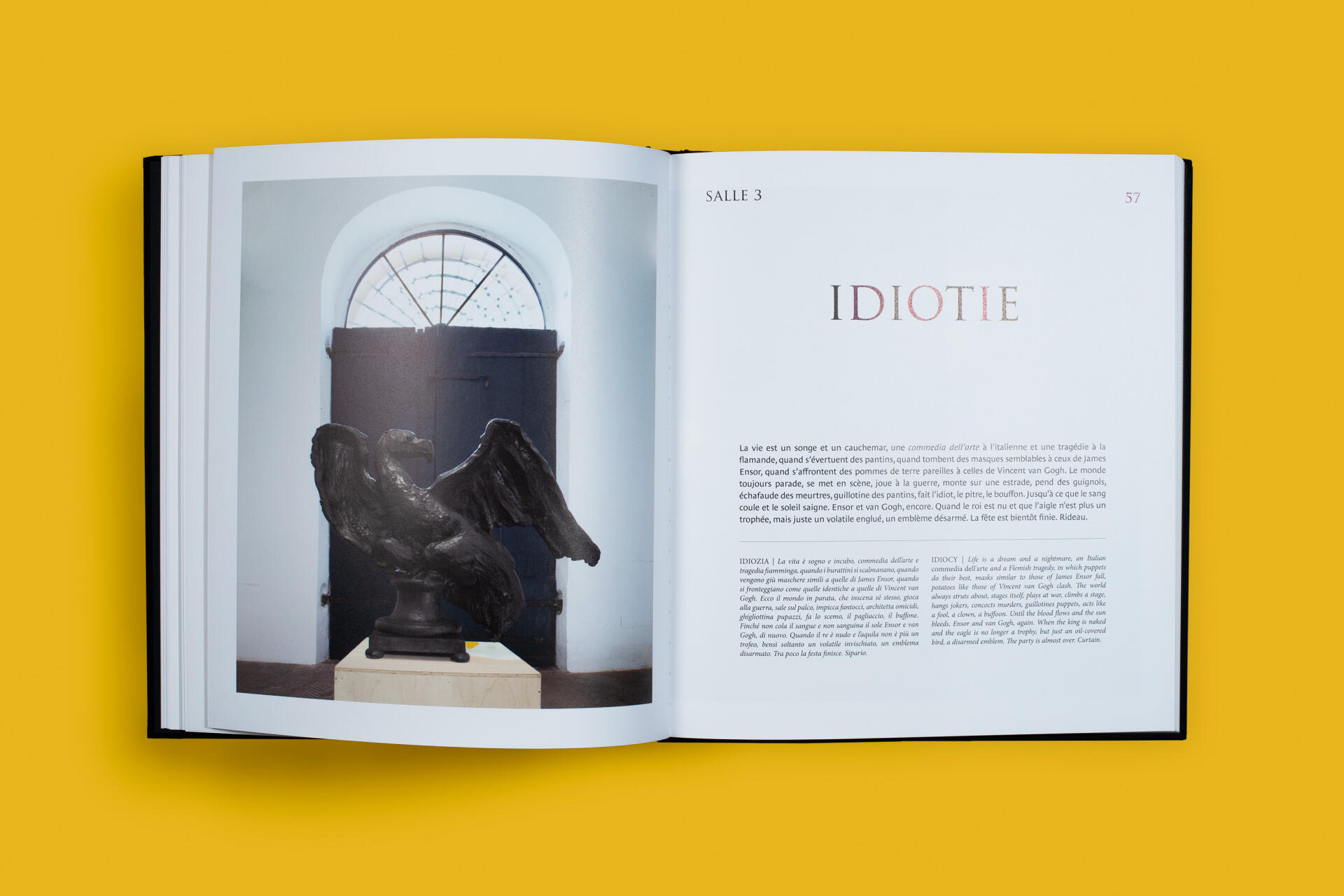

Divided into 12 sections revealing 12 sacrilegious and impure wounds, the book “I PECCATI” plunges the reader into the abyss of a prolific and protean creation, nourished by historical references, hidden connections and intellectual and artistic surprises.

Each part, placed under the ambivalent and dual symbol of a subjective and imperfect morality, is introduced by a text by Colin Lemoine questioning the relationship between Man and sin, between adoration and blasphemy.

In his introductory text, Nicolas Bourriaud returns to the work of Johan Creten, haunted by the notions of good and evil, exorcism and voluptuousness.

“The set of chemical reactions that take place within a living being and enable it to stay alive, reproduce, develop, or respond to the demands of its environment is called the metabolism. In the animal world, colours and motifs are part of this vital dimension. Plumage, hair, scales, skin, livery and carapaces, stripes and spots, can thus all be considered as organs of appearance, as plastic formulas lending an organism, beyond its vital functions and the struggle for survival, a kind of self- presentation. The Swiss zoologist Adolf Portmann (1897–1982) called these motifs ‘phanères’ (skin appendages or adnexa) and even coined the term ‘phanerology’: the science of the appearance of animals. Human beings are not to be outdone. The difference is that they developed by externalizing their faculties, while other species were content to extend their own bodies. Rather than the organic division of labour that is common in the animal kingdom, humans thus opted for a body that is not very efficient, yet infinitely customizable. Thus, if the butterfly creates itself like a painting, humans prefer to produce it on an external support. The artist could then define him- or herself as the butterfly of the human realm: he or she engages in a free and flamboyant production of signs and forms. Art is a specific form of life, which cannot be reduced to the production of objects.”

- TEXTS

Stéphane Gaillard

Noëlle Tissier

Nicolas Bourriaud

Colin Lemoine

Language: French / English / Italian

- FORMAT

29 x 32 cm

Cloth cover

156 pages

- GRAPHIC DESIGN

Catapult, Antwerp, Belgium

Anton de Haan, Frank Kuijpers, Pieter Melis, Tom Van Welkenhuyzen

- PRINT

Graphius, Get, Belgium

- COPIES

1.500 copies

- ISBN : 9782955424544

- Published by

Creten Studio in collaboration with the Académie de France in Rome - Villa Médicis, Almine Rech and Perrotin, 2020